Motorcycle Brakes Understanding Disc and Drum Performance

Motorcycle Brakes are the 2nd most important control system that we have on a bike. Second only to our Tires, Braking Performance can make riding a blast and in the extreme – be the difference between Life and Death. Sure, we’ve all seen the “Speedway Bikes” running in circles at full lock without any brakes (those guys are crazy!), but our real-world experiences have us wanting and needing great performing brake systems. Let’s talk through the science of those Brake Systems so we understand what’s going on a little better.

I have never personally purchased or restored a bike based on which brake system it came with. This may surprise some, but Disc Brakes don’t always mean great performance and Drum Brakes don’t always mean poor performance. I have owned and restored several disc-brake bikes that were horrible brake performers, but some Drum bikes were stellar and delivered remarkable stopping power.

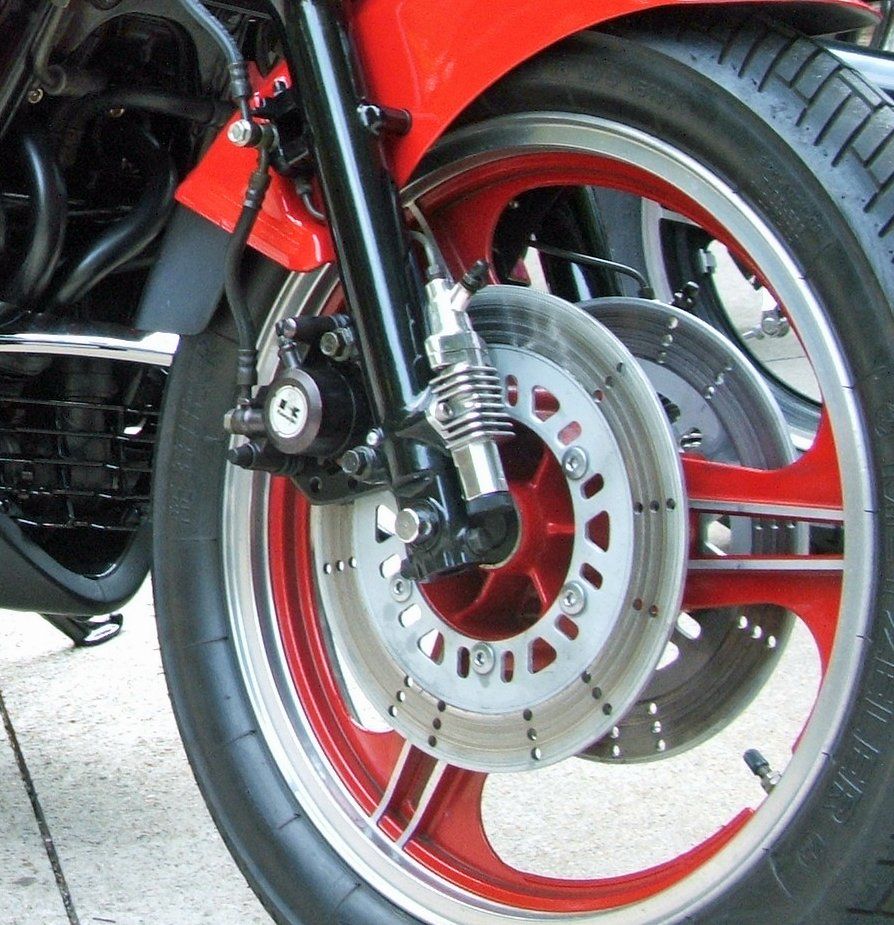

Take my 1974 Suzuki GT750 factory Dual-Disc system – some of the worst front brakes on dry that I’ve ever used and the absolute worst brakes I have ever used when wet. Why? Disc material selection was terrible. Suzuki chose poorly to use a Stainless material for the two disc with more emphasis on looks and resistance to rusting than friction generation. Get them wet and there was no braking.

Suzuki could do much better and did so earlier in 1972 with their GT750 front drum system. The 1972 brakes used the drum/double-leading shoes on both sides! The bike had 4 shoes and two drums in front. Braking performance was amazing. Another star was my 1972 Yamaha R5C 350 with a single double-leading shoes drum system that could rival any vintage disc system that I’ve ever used. That drum system was capable of generating much more stopping power that the best tires of the day could handle. How does this make any sense?

The 3 pieces to the Braking Pie

1) Kinetic Energy (motion of our bike) – measured by calculating the ridden weight times the square of your bike’s speed and divided by 29.9. Let’s take a 500 pound motorcycle and a 200 pound rider going 60 mph – So, we have 700 x (60 x 60) / 29.9 = 84,280 foot pounds of Kinetic Energy that has to be converted.

2) Friction – the resistance between the two brake surfaces (pad and disc or shoe and drum)

3) Heat – while we’d love to leave the heat out of our braking systems equation, this by-product comes from the friction between those very necessary braking surfaces. Energy doesn’t just disappear anywhere on earth, so the conversion from Kinetic Energy to Heat is all we have.

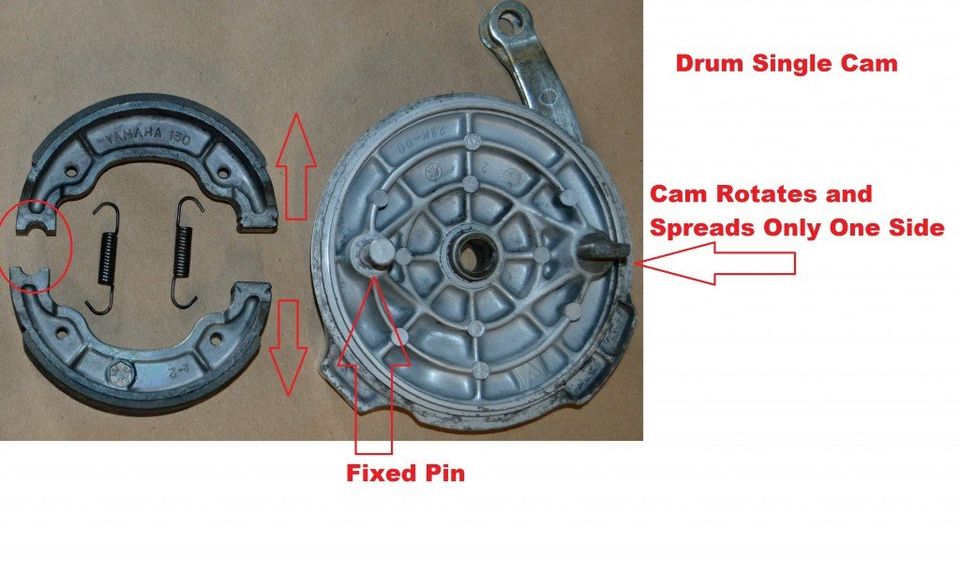

• Drum Brakes with Shoes that have the same curvature and “fit” their Drums squarely and effectively from the initial application to full-pedal can certainly equal the stopping power of Disc Brakes having the same pressure and surface area. This is true as long as the friction material is equally effective at generating friction. Getting shoes to fit their drum takes a little work (arcing and regular, careful adjustments).

These adjustments are especially important with double-leading shoe systems (front brakes). The term double-leading shoe brakes refers to a system that expands the shoes on both ends. When properly adjusted, these can apply a lot of friction and performance.

So Why Disc Brakes?

• Heat. Heat is the bad, unwanted ingredient in our Braking Pie!

• Brakes work as long as friction can be generated, but frequent, continuous, and heavy applications of our brakes convert that Kinetic Energy to Heat. Once our brakes get hot, they can no longer generate the same friction. Performance fades – more heat, less brakes.

• The Disc is exposed to fresh air so it has much better cooling. The drum on the other hand is blocked and the friction surfaces are not cooled sufficiently during repetitive or prolonged use. This heat can be transmitted into the bearings and seals which can shorten bearing lubrication and bearing life.

• The Pad and Disc system stay in very close proximity and even light contact, so a cleaning and wiping effect is continuous. Drums can hold and circulate debris and loose shoe material which can impair performance.

So Why the Front Wheel?

• Weight Transfer and Traction. Once the brakes are applied, a greater proportion of the weight is transferred to the front wheel. After this transfer, the front tire and brake can handle 60~90% of the total stopping force of your bike.

Forget tire size for a moment. This transfer of weight rear-to-front causes the front tire to flatten a little and both the surface area and surface tension are increased dramatically. With this increase in surface tension, the tire is now capable of applying tremendous stopping power safely.

This is why the front wheel gets most of the brake system. Whether it’s double-leading shoes in a large drum, single disc over a drum rear, or those dual-disc set-ups, it the front tire that we must rely on for the biggest part of our stopping performance.

All Rights Reserved | RRR Tool Solutions.